The following article originally appeared in The Guardian in 2014, but is still relevant to this day!

As I wrote after the release of Don Jon, this film is yet another example of a film where the women only exist in order to teach the men a lesson.

Read More…

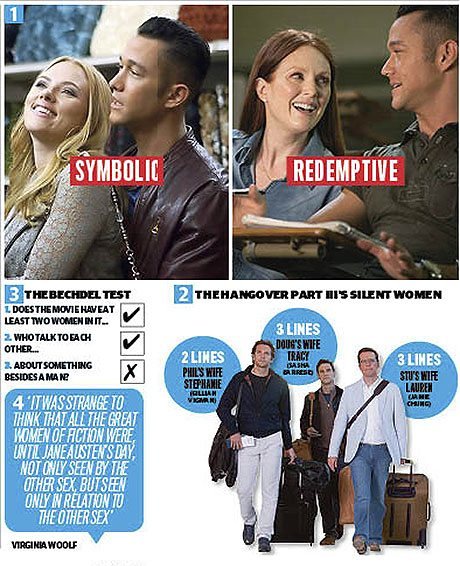

In his supremely cocky directorial debut Don Jon, Joseph Gordon-Levitt plays the eponymous Jon, a self-professed porn fanatic who openly acknowledges his preference for internet porn stars over “real pussy” – a telling synecdoche he applies to the female gender at large. And who can blame him, given the sorry assortment of real pussy Gordon-Levitt surrounds his creation with. Of the two anaemic love interests in the film, Scarlett Johansson’s selfish Joisey girl Barbara exists solely to illustrate what’s wrong with Jon’s taste in women, while Julianne Moore’s older, wiser Esther is merely a catalyst for his inevitable redemption (Graphic 1).

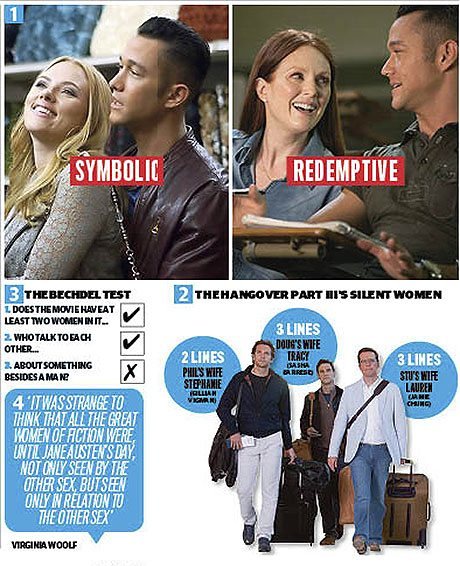

A lot is made of the scarcity of female characters in Hollywood, but equally troubling is the nature of those who do exist. Women like Barbara and Esther are indispensable to films like Don Jon, but only because they allow us to better understand the men at the centre of the story. The ragtag heroes of The Hangover trilogy would’ve been nothing without their eternally weary spouses (Graphic 2), whose perpetual tut-tutting reinforced the idea of Phil, Stu, Alan and the other one as downtrodden everymen, rather than unfeeling, noxious dickheads.

When cartoonist Alison Bechdel devised the Bechdel Test (Graphic 3) in 1985, she asked her readers to question the infrequency of movies in which female characters talk to one another about their own concerns, rather than those of the men in their lives. Today, fewer than 40% of films released in the UK pass this simple test, while the biggest blockbusters have even lower success rates; recent global smashes Pacific Rim, Monsters University and Star Trek Into Darkness are all notable fails. Don Jon does pass the test, but only on an inglorious technicality: the film’s non-male dialogue consists of a single two-line exchange in which one woman offers to help another in the kitchen.

Incredibly, the situation is worse today than it was a century ago. In the 1920s, there were almost as many female screenwriters in Hollywood as male ones. Writers such as Frances Marion and Anita Loos were among the most revered in the industry, and brought a raft of complex, multi-dimensional female characters to the big screen. But as the film industry swelled with the advent of sound and colour, women were increasingly squeezed out of such powerful positions, and into roles that deferred to their male colleagues. Their on-screen counterparts also took the backseat (4) and have been fighting to regain ground ever since.

When Jon finally learns to see women as more than objects in Don Jon, it’s at the behest of his sister Monica, played by 21 Jump Street’s Brie Larson. Up until that point, she’s been a silent figure around the family dinner table, permanently fixated on her omnipresent iPhone. She breaks this vow of silence only to warn Jon not to see women purely for what they can offer him. Then, with nothing left to offer him, she recedes quietly out of view.

###

And, perhaps worse in more recent developments, last month, The Hollywood Reporter drew attention to an unsettling trend–several TV shows killed off female characters: Sleepy Hollow caps a deadly week on the small screen that featured multiple series regulars and recurring guest-stars being killed off, as broadcast and cable networks alike use the plot point to draw eyeballs and make headlines. Gone are Arrow‘s Laurel Lance (played by Katie Cassidy); Vikings‘ Yidu (Dianne Doan) and Kwenthrith (Amy Bailey); Empire‘s Camilla (Naomi Campbell) and Mimi (Marisa Tomei); andThe Americans‘ Nina (Annet Mahendru), as well as one of 11 stars on AMC’s The Walking Dead, which ended with a massive cliff-hanger.

Erotic Cinema For Discerning Adults

Erotic Cinema For Discerning Adults Anonymous Adult Search

Anonymous Adult Search